Preface

This article takes a peek into what HLSL shaders in Unity3D are from a coder’s perspective, and how to understand them enough to get a practical grasp on making them do what you want. This won’t really teach you the hard low-level details, but you should be able to understand each section of a shader and why each part exists when you’re done. So with that, let’s get started!

Part 2: Parts of a Unity shader

Before we jump in, let’s me make sure we’re all on the same page. For this article we’ll be using the following shader:

Shader "StarcubeLabs/BasicVertFrag"

{

Properties

{

_MainTex ("Texture", 2D) = "white" {}

}

SubShader

{

Tags { "RenderType"="Opaque" }

LOD 100

Pass

{

CGPROGRAM

#pragma vertex vert

#pragma fragment frag

// make fog work

#pragma multi_compile_fog

#include "UnityCG.cginc"

struct appdata

{

float4 vertex : POSITION;

float2 uv : TEXCOORD0;

};

struct v2f

{

float2 uv : TEXCOORD0;

UNITY_FOG_COORDS(1)

float4 vertex : SV_POSITION;

};

sampler2D _MainTex;

float4 _MainTex_ST;

v2f vert (appdata v)

{

v2f o;

o.vertex = UnityObjectToClipPos(v.vertex);

o.uv = TRANSFORM_TEX(v.uv, _MainTex);

UNITY_TRANSFER_FOG(o,o.vertex);

return o;

}

fixed4 frag (v2f i) : SV_Target

{

// sample the texture

fixed4 col = tex2D(_MainTex, i.uv);

// apply fog

UNITY_APPLY_FOG(i.fogCoord, col);

return col;

}

ENDCG

}

}

}

This shader is the basic shader that Unity generates when you request a basic Unlit shader. It is a Vert Frag Shader that simply applies a texture, with no calculated shading.

We’ll be using this particular shader for the remainder of this article.

Everything has its order / Breaking it down and translating the parts.

So, if you’ve never looked at an HLSL shader, most of the code we’re looking at probably looks like vaguely C# gibberish right? Well, let’s break it down and color code it all to make this easier.

To me, HLSL is easier to understand if you think of it kind of like a potion brewing process. From the top to the bottom, there are certain steps that have to happen before other steps can happen - everything has an order. To add onto that, specific things must be declared to help clarify the intent of the shader before you start. Your basic shader can be split up into about 6 important parts:

P2-A: Input Variable Declaration

Shader "StarcubeLabs/BasicVertFrag"

{

Properties

{

_MainTex ("Texture", 2D) = "white" {}

}

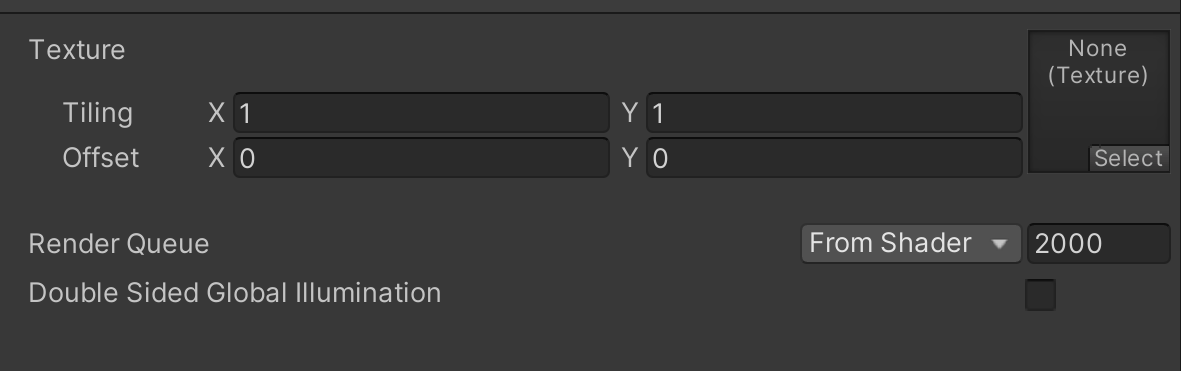

The first part of writing a shader is declaring what parts you want to be dragging in or handling from the Unity side. This includes everything from Textures, Colors, pure float or int Values, or even Ranges between two numbers. For our example, this declaration gives us one texture to be used in the material inspector:

Our declared Texture as seen in the inspector

Our declared Texture as seen in the inspector

You can declare as many things as you want here, but be aware that simply declaring them here doesn’t make them usable in your shader. You’ll have to manifest those variables later to make them usable by your shader.

P2-B: Tag Attribute Declaration

SubShader

{

Tags { "RenderType"="Opaque" }

LOD 100

This section of the shader is kind of unique in that its function is to declare how many resources your shader is going to use as a whole via including descriptive Tags and other Sub-Attributes. Depending on what is declared here, the shader will be wholly capable or incapable of specific things. This example shader we are looking at is currently not tagged to be able to use Transparency or any alpha channel of any kind.

If, for example, we wanted a shader that was capable for transparency, the Tag section would look like this:

SubShader

{

Tags { "RenderType" = "Transparent" "Queue" = "Transparent" }

LOD 100

ZWrite Off

Blend SrcAlpha OneMinusSrcAlpha

CGPROGRAM

Tags work by ensuring that resources that shaders do not need are not allocated to them, increasing efficiency. I’ve colored this section gray because, thankfully, nothing declared here will need to be manifested later - this section of the code is self-contained.

Unity’s documentation on what tags can be used can be found here.

P2-C: Shader Attribute Declaration

Pass

{

CGPROGRAM

#pragma vertex vert

#pragma fragment frag

// make fog work

#pragma multi_compile_fog

#include "UnityCG.cginc"

Shader Attributes are declared using what are called Pragma Directives. There are multiple types, but the main ones we usually are concerned with as Unity developers are #pragma vertex vert, #pragma fragment frag, and #pragma surface surf (for Vertex, Fragment, and Surface shader types respectively). The format for Pragma Directives is #pragma <pass type> <what you'd like to name the pass's method> - this means for our shader that later down the line for the Vertex pass we will be writing a vert() method and for the Fragment pass we will be writing a frag() method.

Other Pragma directives are more like flags and don’t have an associated method we will have to write. #pragma multi_compile_fog simply says that our shader will be able to access fog calculations down the line.

Lastly, we have our #include directives, which simply allow us to import the contents of other files for our own use in this file. #include "UnityCG.cginc" is a special include which means that its presence in our Unity project is not required for us to import it unlike other includes. It’s actually included with our installation of Unity, so any Unity project can import it.

Unity’s documentation on what Pragma Directives can be used can be found here

Unity’s documentation on what the UnityCG.cginc is and what it includes can be found here

P2-D: Pragma Attribute Manifestation

struct appdata

{

float4 vertex : POSITION;

float2 uv : TEXCOORD0;

};

struct v2f

{

float2 uv : TEXCOORD0;

UNITY_FOG_COORDS(1)

float4 vertex : SV_POSITION;

};

Earlier, we mentioned that for the Pragma Directives we defined (vert and frag) we’d have to write methods for them. This section helps define what data those methods take in. Each struct is kind of like a class that holds multiple variables of different types within. Our appdata struct has a vertex variable that is of type float4, which means it is an array of size 4 that holds 4 floats. uv is the same, it is an array of size 2 that can hold 2 floats.

These structs don’t only define the types of data the method uses as input, but it also defines the pre-calculated 3D model or world data that should be included in the shader. But what does that mean?

You’ll see that vertex has the POSITION attribute tacked onto its end. What that signals to Unity is that this float4 vertex is the designated holder of the Positional Vertex Data of the 3D model this shader is applied to. That means, any Vert shader that wants to modify the position of a 3D model’s vertices needs the data held within this vertex variable. In the same way, the uv variable’s attribute TEXCOORD0 means that the 3D model’s UV Coordinates are now stored within the uv variable.

Down in the v2f struct, vertex has an SV_POSITION attribute - this means that it should take into account the Unity Camera’s clip distance. The free-floating UNITY_FOG_COORDS(1) is a bit more complicated. It is a command that places the pre-calculated Unity Fog data that we called for with the #pragma multi_compile_fog Directive into TEXCOORD1. We’ll be able to use this data later down the line.

But what are structs even for? (Transferring data between passes, actually.)

One thing you’ll notice is that there are two structs. The reason for this is that each Directive we need a struct. But there’s more to it than that as well - if you’ll recall from our previous part that the Vert Pass runs before the Frag Pass and that data in the Frag Pass needs to come from the Vert pass. This section that we are looking at is a key part of the process of passing the data between those passes. You’ll notice that both appdata and v2f both contain a uv variable and a vertex variable. We set up our first struct appdata to work with the vert method, and within that vert method we are going to give the the data stored in appdata to a v2f object to be used in the frag method. That’s right. vertex to vertex, uv to uv.

v2f actually stands for Vert To Frag - it’s an struct specifically meant to bring data from the Vert pass to the Frag pass. (In this case, v2f can be replaced with literally any text but v2f is traditionally used as it is the most descriptive.)

You’ll see this in action later, when we write the actual vert() and frag() methods.

Unity’s documentation on *Semantic Attributes can be found here*

P2-E: Input Variable Manifestation

sampler2D _MainTex;

float4 _MainTex_ST;

This section is actually pretty simple. All the variables that we declared over in Section A now officially get to exist. If you declared a variable at the top of the shader, set it up with an actual variable here. Floats and Ints are stored in their respective types. Colors are stored within Float4 or Fixed4 types, depending on how much they are expected to change during runtime. And Range types can be stored in either Ints or Floats depending on how they are declared.

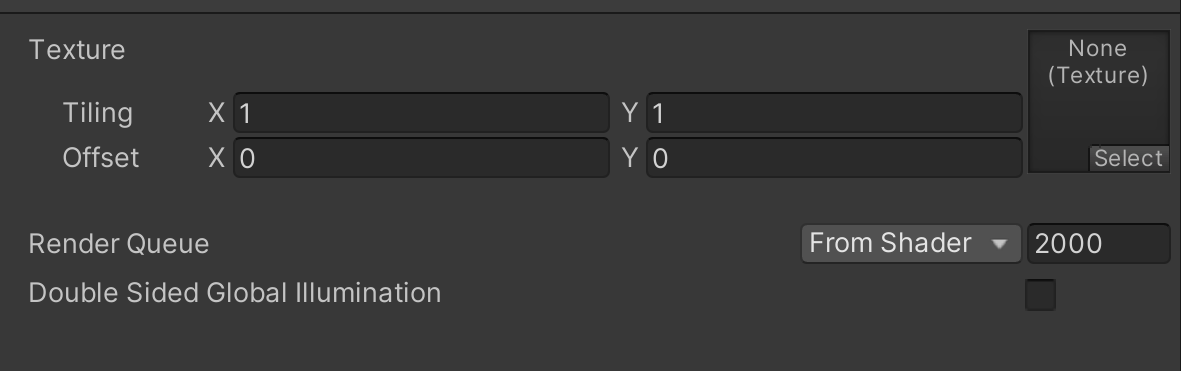

However, take note: Texture types have some special rules when you make variables for them. They are stored within sampler2D types instead of float4 types when they are not being declared inside a method. ALSO, whenever you set up a texture, you also can set up a Special Texture / _ST variant of that texture in a separate variable (which is just the name of variable with _ST tacked onto the end). The _ST variant contains all of the transform data of its parent texture, with the tiling value in the [x, y] section of the float4 array and the offset value in the [z, w] section of the float4 array.

The Offset and Tiling data can be seen here, on the left.

The Offset and Tiling data can be seen here, on the left.

Once all of our inputs have been manifested here, they will be usable within the methods we will write down at the bottom of the file.

All of the documentation on Special Textures and other special properties can be found here.

P2-F: Pragma Method Manifestation

This is it. Where it all comes together. The color coding here is purple, because it involves every other part of the shader we’ve looked at so far.

It works in two parts. The Vert method takes in any pre-calculated stuff we’ve set up for our first appdata struct, makes any geometry changes we want, and then passes that data to a v2f struct that it returns. The Frag method takes in that v2f struct that the Vert method returned, and does any calculations it needs before returning a fixed4 color back to the Unity engine.

The vert() Method

v2f vert (appdata v)

{

v2f o;

o.vertex = UnityObjectToClipPos(v.vertex);

o.uv = TRANSFORM_TEX(v.uv, _MainTex);

UNITY_TRANSFER_FOG(o,o.vertex);

return o;

}

You can see here that our vert method is of return type v2f, and takes in an appdata struct that we call v. Inside the method, we make a new v2f struct we call o - and then we set the o version of our variables to the v version of our variables, with some additional calculations. o.vertex is set to v.vertex while taking into account Clip Position, o.uv is set to a Texture Transform of v.uv with respect to the Main Texture, and o’s fogCoord (which is an included thing we get for declaring we’re using fog in our earlier sections) is combined with all the precalculated data and v.vertex. Finally, o is returned to be picked up by the frag method later.

This is the most basic vert method you can make, and pretty much every other vert you see will be in some way built on what you see here.

The frag() Method

fixed4 frag (v2f i) : SV_Target

{

// sample the texture

fixed4 col = tex2D(_MainTex, i.uv);

// apply fog

UNITY_APPLY_FOG(i.fogCoord, col);

return col;

}

The frag method is the final step of the shader. We take the v2f struct that our vert method prepared earlier, do some work with it, and then return a single pixel of type fixed4. Also, our method has the attribute of SV_Target, to make sure it complies with the Unity Camera Clip Position.

For this method, it’s very simple. We simply get the color of the pixel on the main texture at the current coordinates, apply the fog we got from the vert method to it, then return it.

In the same way as before this is pretty much one of the most basic frag methods we can make, and just about every one you see after this point is going to look like a more complicated version of this one.

Epilogue

Now that we’ve looked at each individual section of a basic shader, we can start looking at other tips, tricks, and shader variants!

- Spex from Team Starcube